Distortion Fields in OpenSCAD: Computationally Expensive And Not Entirely Satisfying, But Good To Know Anyway

This is the second in an occasional series about 3D models and prints that I design. The code for this post, and some 3D models, are available in the associated github repo. The code for this post was largely inspired by the bending procedures posted to Thingiverse by the user flavius

In the previous post, I described how to use the children module in OpenSCAD

to repeat models in regular patterns–specifically, to make cylindrical tiled

vase sculptures. This post will explore what I call distortion fields–modules

that apply non-homogenous transformations to their children. A word of

warning: these techniques are extremely computationally expensive if you want

good results in many common cases. They also tend to require some massaging

to fit each specific case, so it’s worth understanding how they work. The good

news is that with a few helper functions, distortion fields are fairly simple

to implement, so it’s mostly a matter of coding for 10 minutes, pressing

“render,” and going to get a beer.

A good example of where a distortion field can be useful is in a model of an airplane wing (warning: I know nothing about actual aerodynamics). Wikipedia gives me a nice cross-section of an airfoil.

Image credit: Olivier Cleynen

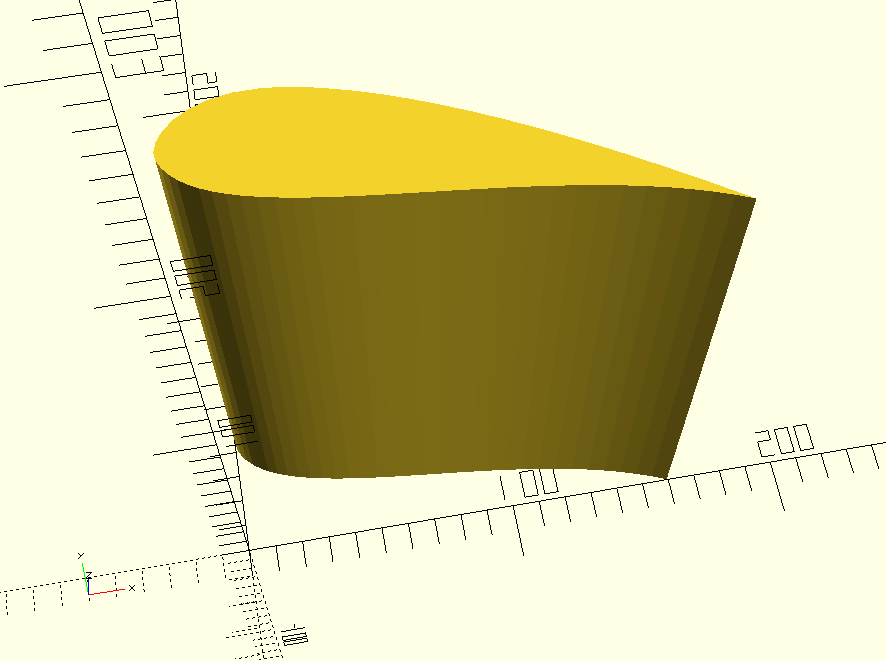

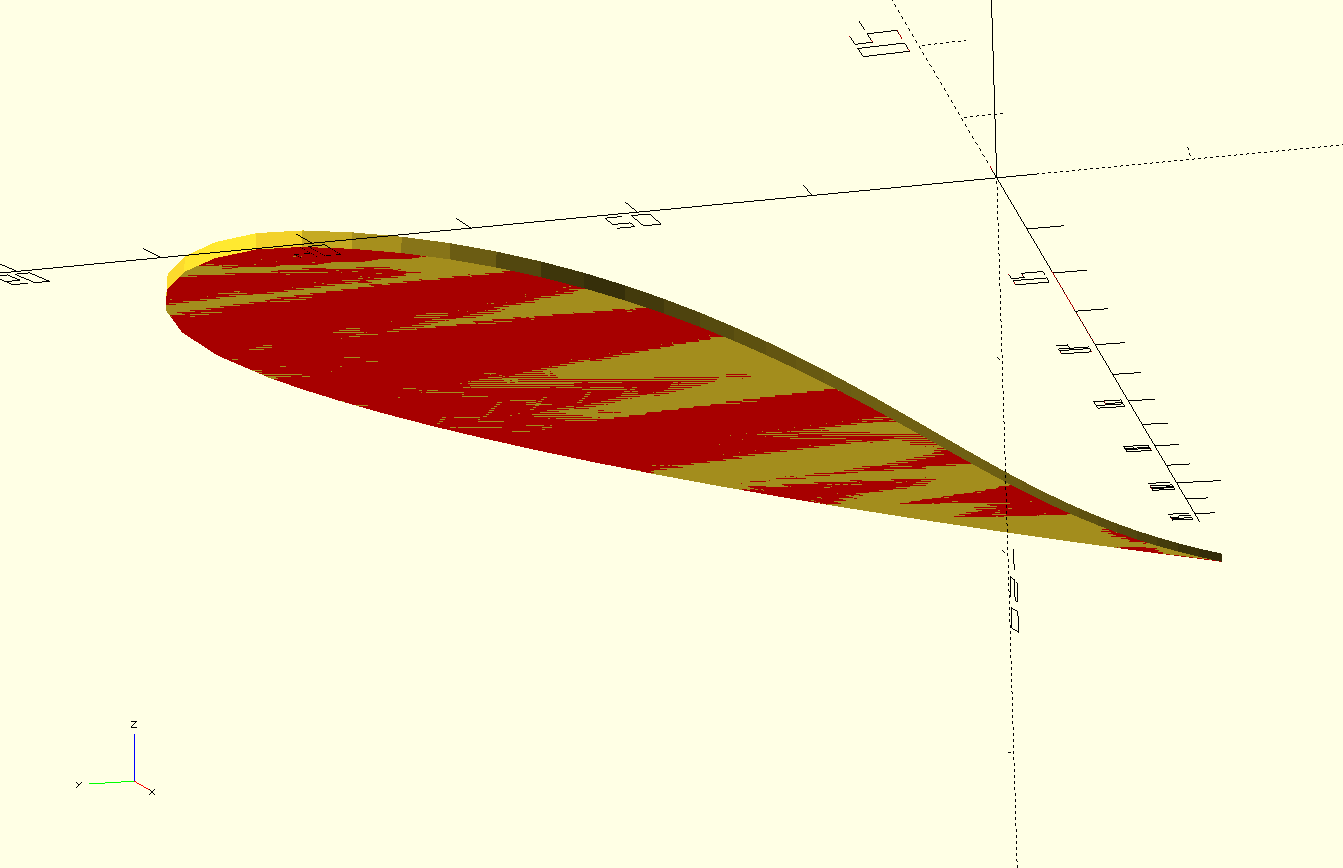

I’d like to take that cross-section and use linear_extrude to stretch it out

into a wing.

linear_extrude(height = 203) import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

Airfoil cross section extruded

But that’s not right. Wings are wider at their base, where they connect to the fuselage, and narrower at their tip. They’re also usually more triangular, in top-down view, than rectangular. What I need to make this extruded airfoil into a wing is to apply a kind of “scale-gradient,” so that it gets smaller from one end to the other, and also a “translation-gradient” so that it sweeps back from the big end to the small end.

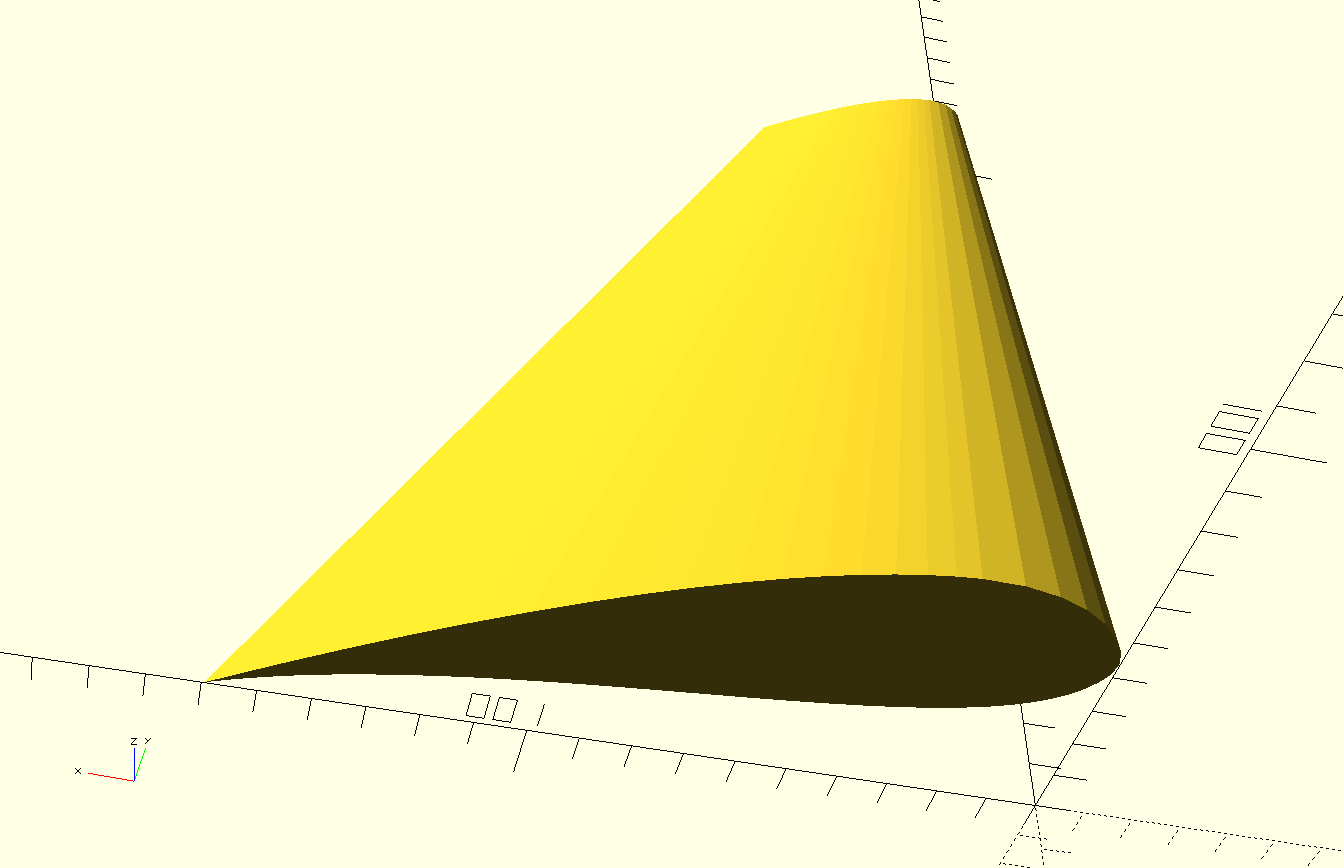

The linear_extrude function does have a scale parameter, which will

help a little bit in this case.

module scaled_extruded_airfoil() {

linear_extrude(height = 203, scale=[0.3, 0.3]) {

import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

}

}

scaled_extruded_airfoil();

Airfoil cross section extruded and scaled along its length

This is good, but it doesn’t give you a way to control where the end of the extruded

shape “lands.” The leading edge of the wing is a straight line, based on some internal

representation of the origin of the 2D shape being extruded. I’d like the leading

edge of the wing to be swept back. Also, in many cases the model to be scaled will

be 3D, so this nice linear_extrude scaling trick won’t be available. Or I might

want to scale an object in a way that is not linear along its length, and this

trick won’t be suitable.

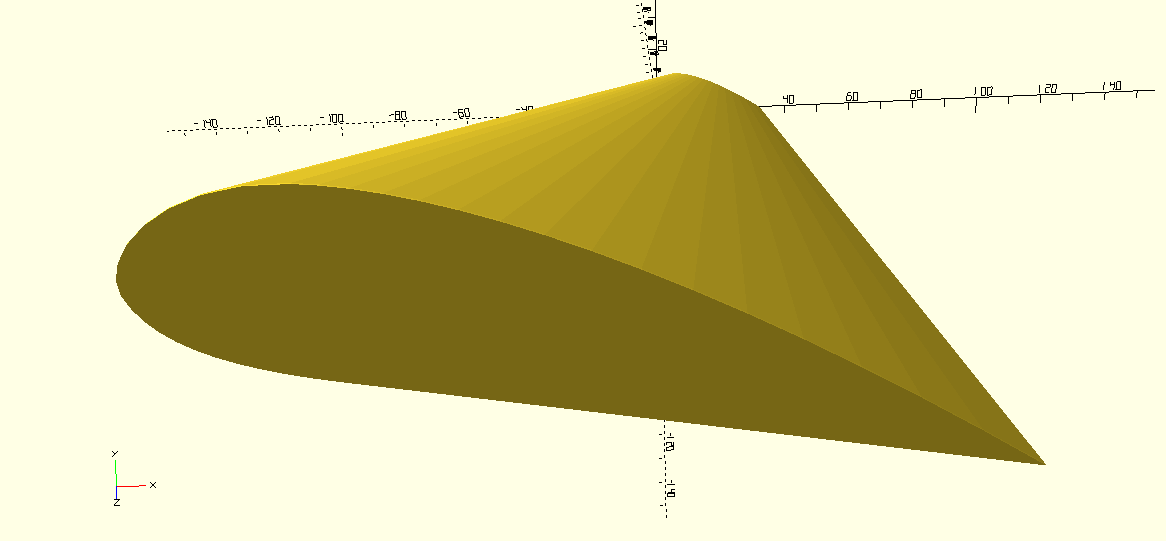

One way to try to achieve a “scaled and swept-back” effect is with a clever use

of hull to unite a big, thin airfoil cross-section with a smaller cross-section

translated one wing-length away. This is a good approach when it works, because

it is far cheaper, and the result far smoother, than using a distortion field, as we’ll

see. But hull has its own price: it eliminates any concave details in the

model. Holes and indentations, like the scooped bottom of the airfoil, do not

survive.

module hull_wing() {

hull() {

linear_extrude(height = 0.5) {

scale([0.2, 0.2, 1]) import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

}

translate([-100, 0, 203]) {

linear_extrude(height = 0.5) import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

}

}

}

hull_wing();

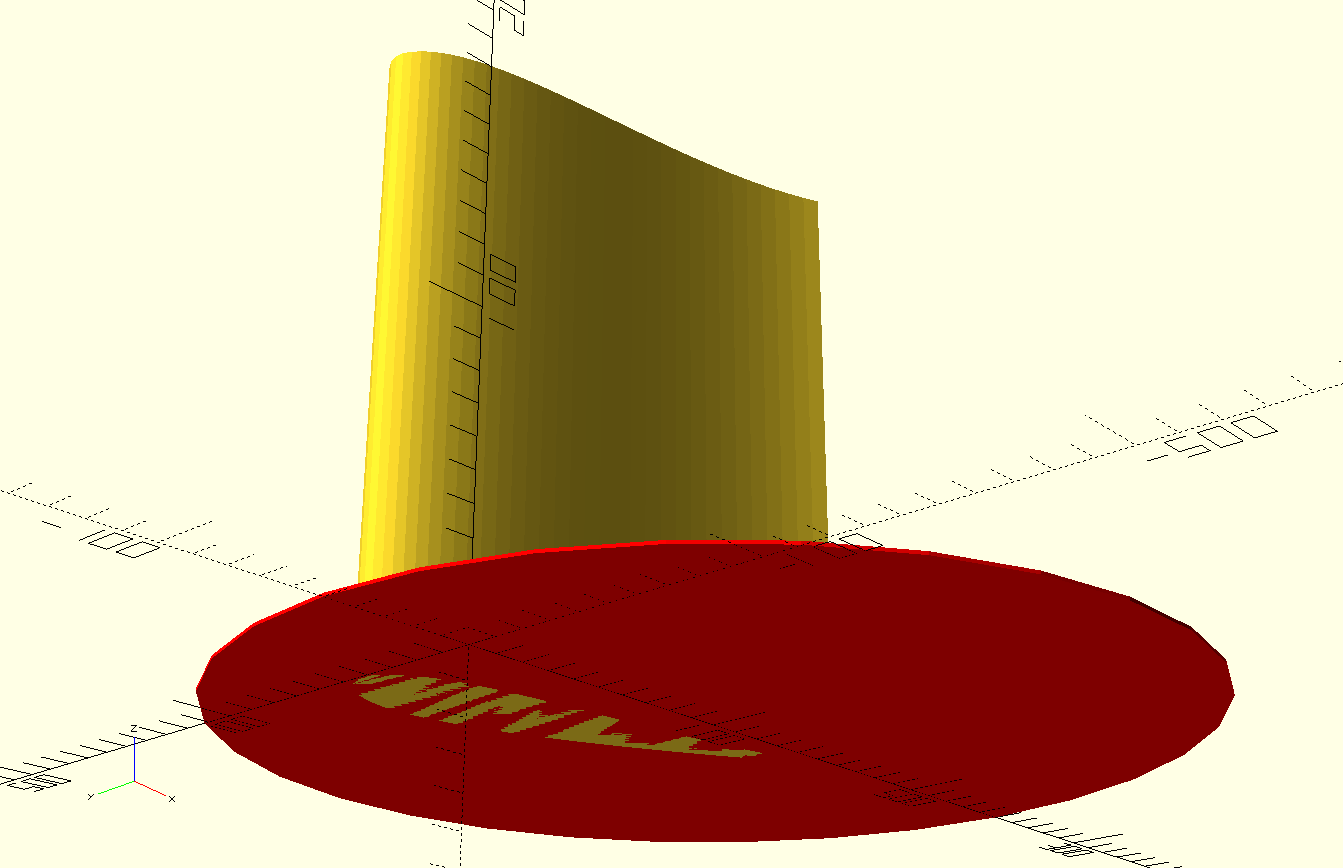

The hull operation flattens the previously-concave underside of the wing

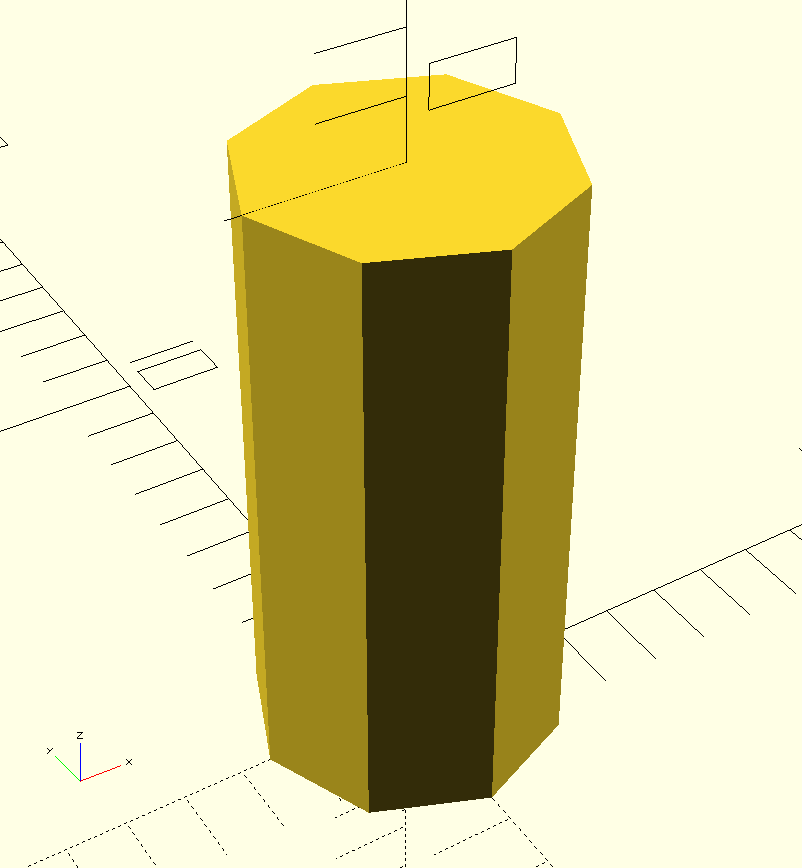

As an introduction to how distortion fields work, let’s look at how OpenSCAD models cylinders. If I make a simple cylinder, the result will be a prism with very obvious facets, not a smoothly-curved one.

cylinder(10, d-5);

A default cylinder is not very curved

If I want a cylinder with a smooth surface, I can manually specify the

number of facets using the $fn parameter.

cylinder(10, d-5, $fn=30);

With 30 facets, this looks more like a cylinder.

The best number of facets is the lowest number that still looks like a curve in the eventual object. I’m usually making models for 3D printing, and I know that when each facet is small enough, the printer is just going to print a smooth curve. The central idea is that small-enough details blend together.

To apply that idea to the wing model, I can imagine applying successive

transformations to arbitrarily-small slices of the wing, so that the

final result would be a relatively-smooth approximation of the shape I wanted.

I could make thin wing slices with successive calls to linear_extrude, but

for the sake of demonstration I’m going to pretend that I only have a 3D

model to work with, which is often the case in practice. I can take a short,

wide cylinder (really any shape that can surround the 2D wing shape) and

superimpose it on the wing.

module extruded_airfoil_cylinder_superimposed() {

linear_extrude(height = 203) import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

color("red") translate([100, 0, 0]) cylinder(1, d=300);

}

extruded_airfoil_cylinder_superimposed();

Now, if I take the intersection of these shapes, I should be left with a slice of the wing that has the same (thin) height as the red cylinder.

module intersection_airfoil_cylinder() {

intersection() {

linear_extrude(height = 203) import("../dxf/airfoil.dxf");

color("red") translate([100, 0, 0]) cylinder(1, d=300);

}

}

intersection_airfoil_cylinder();

A thin slice of the airfoil where it intersects with the cylinder

There’s a special kind of tipping point I always look for in any technical project. It’s the point where I’ve figured out, not exactly how to do the thing I want, but enough to know that it can be done. Sometimes the process of getting to that tipping point is called “driving out risk,” with the idea that once you hit it, there are no more risks that have the potential to fundamentally prevent what you want to do. After I know that I have all the building blocks to realize my idea, my next step is to get a working version, no matter mow ugly. Once I have a working version I can refine it as necessary (but it’s surprising how often an initial version works for all the cases that matter!).

At this point I have all the building blocks I need to make the wing.

- I can make a thin slice of an object if I know its approximate dimensions in X and Y.

- I can scale and translate a thin slice of an object.

- I can use the

childrenmodule to refer to an object to be distorted.

In pseudocode, the algorithm I want to implement looks like:

// This isn't real code!

// start and end are [x, y, z] vectors for the translation.

module translate_field(diameter, height, steps, start, end) {

for (i=[0:steps - 1]) {

// take the intersection of the transformed object and

// a cylinder to cut out a thin slice

intersection() {

// apply the appropriate transformation to the object.

// note that the interpolate function doesn't

//exist in OpenSCAD, I need to write it myself

translate(interpolate(start, end, steps, step)) {

children(0);

}

// translate a thin cylinder to the correct height for this

// step on the original object

translate([0, 0, i * (height / steps)]) {

cylinder((height / steps), d=diameter);

}

}

}

}

Functions in OpenSCAD have a kind of odd syntax. I haven’t looked

into it in depth, but when I need to write one I often refer to

the documentation.

Suffice it to say that the interpolate function can be implemented

this way:

function interp(start, end, steps, step) =

let (pct = step / steps)

[

start[0] + (pct * (end[0] - start[0])),

start[1] + (pct * (end[1] - start[1])),

start[2] + (pct * (end[2] - start[2])),

];

This is a good linear interpolation function, but I actually don’t want to permit translation in the Z-axis, so I can write a helper function that prevents it.

function xy_interp(start, end, steps, step) =

interp([start[0], start[1], 0], [end[0], end[1], 0], steps, step);

Now I should be able to use this function to complete the translate_field

function and use it to modify the scaled extruded airfoil.

// start and end are [x, y, z] vectors for the translation.

module translate_field(diameter, height, steps, start, end) {

for (i=[0:steps - 1]) {

// take the intersection of the transformed object and

// a cylinder to cut out a thin slice

intersection() {

// apply the appropriate transformation to the object.

// note that the interpolate function doesn't

//exist in OpenSCAD, I need to write it myself

translate(xy_interp(start, end, steps, i)) {

children(0);

}

// translate a thin cylinder to the correct height for this

// step on the original object

translate([0, 0, i * (height / steps)]) {

cylinder((height / steps), d=diameter);

}

}

}

}

module scaled_translated_wing(steps) {

translate_field(600, 203, steps, [0, 0, 0], [100, 0, 0]) {

scaled_extruded_airfoil();

}

}

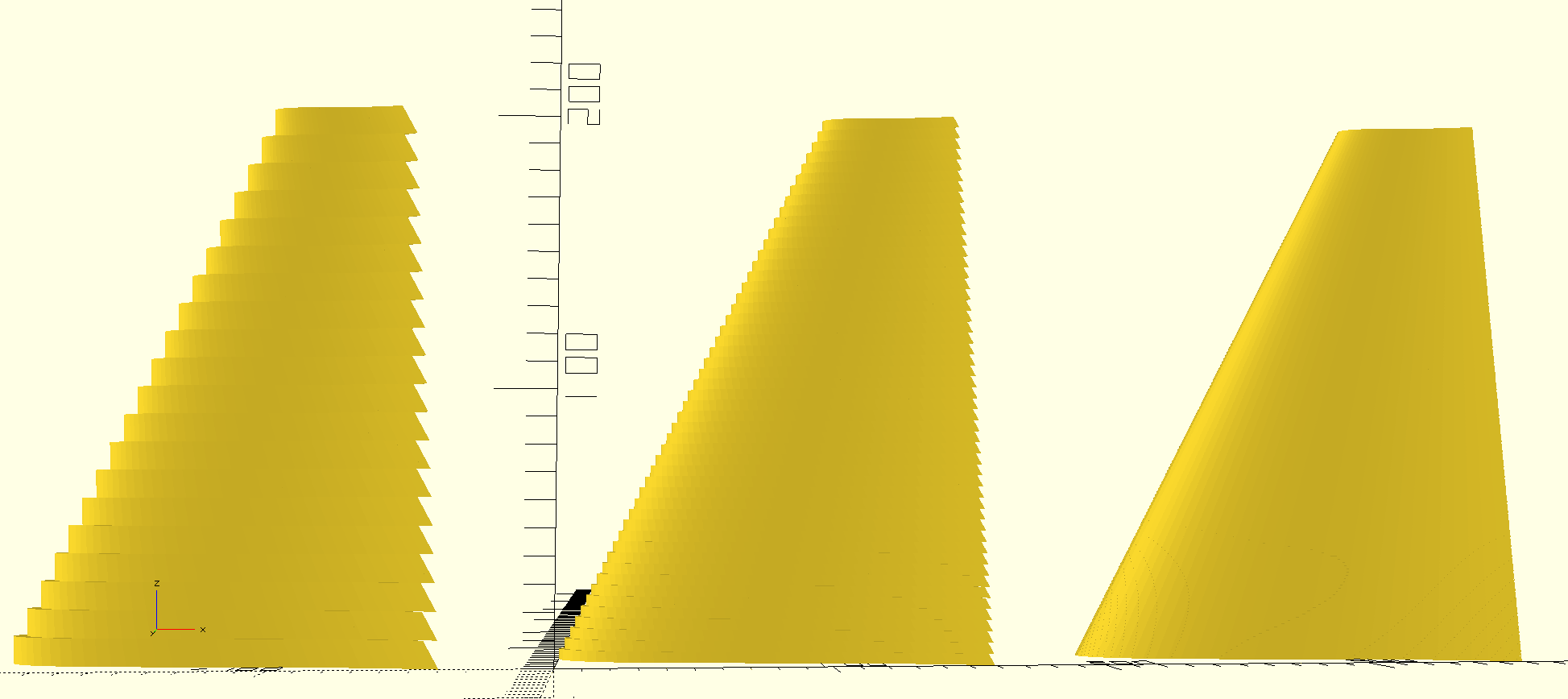

translate([-200, 0, 0]) scaled_translated_wing(20);

scaled_translated_wing(50);

translate([200, 0, 0]) scaled_translated_wing(500);

Comparison of 20, 50, and 500 steps. Higher numbers of steps make it look smoother at the cost of longer rendering times

As the figure shows, it’s possible to approximate a smooth distortion if I’m willing to pay a significant price in rendering time. As I said before, this can be an expensive technique, but its flexibility, and the fact that it can be applied to arbitary 3D shapes sometimes make it the best tool for the job.

Note that a big factor that affects rendering time is the number of parts that a model has. Each step consists of about three parts for rendering purposes:

- the whole wing, translated;

- the cylinder that intersects it

- the intersection of the wing and the cylinder

That means that for 500 steps, OpenSCAD is rendering 1500 objects. This is

why it’s often better to construct a custom distortion field procedure

rather than “stacking” a set of generic ones. For instance, if I wrote a

scale_field module that did a linear scaling of an object the same

way the translate_field does a translation, and I had an object that I

wanted to both scale and translate, I could use the following code

module scaled_translated_wing(steps) {

translate_field(600, 203, steps, [0, 0, 0], [100, 0, 0]) {

scale_field(600, 203, steps, [1, 1, 1], [0.4, 0.4, 1]) {

extruded_airfoil();

}

}

}

scaled_translated_wing(500);

But this would be a Bad Idea, because first the scale_field would

take the wing and generate 1500 parts from it, and then the translate_field

would do the same, for a total of 3000 parts. In a moderately complicated

model, where an object like this wing might be repeated a few times, the

rendering time would quickly become infeasible. Instead, it would be better

to write a custom scale_and_translate field that would apply both

transformations in a single pass.

Obviously, this technique is only a tool for situations where OpenSCAD doesn’t have a better option built in. But in those situations it provides unparallelled flexibility. It’s especially useful when you want to define a custom interpolation function. With a quadratic interpolation you can achieve a curved scaling or translation effect, which is often useful when you want a seamless transition between individual pieces that are meant to be screwed or glued together. It’s also nice to have the ability to apply these kinds of effects after you have designed the individual parts, so that the design of the part itself isn’t burdened with the detail of how it attaches to the rest of the system.

All the code for this post is available in the associated github repo. If you liked it, I encourage you to download a copy of OpenSCAD and try it out for yourself.